For us xooglers, Kubernetes is the closest thing in the outside world to Borg. I don’t have any immediate need to use it, but twice now I have decided it would be a fun thing to tinker with. Both times, I’ve run into issues with the getting started guides. This post is to note the work-arounds for the problem I encountered.

I’m pretty sure that if I were willing to pay Google some money to learn about Kubernetes on Google Container Engine, it would all work just flawlessly. Unfortunately, I’m cheap and I want to learn about Kubernetes using Vagrant on my laptop. Unsurprisingly, this getting started guide is woefully incomplete. It has you create a replicated nginx setup where you cannot even reach any of the 3 replicas and then it closes with what I take to be a sarcastic, “Congratulations!”

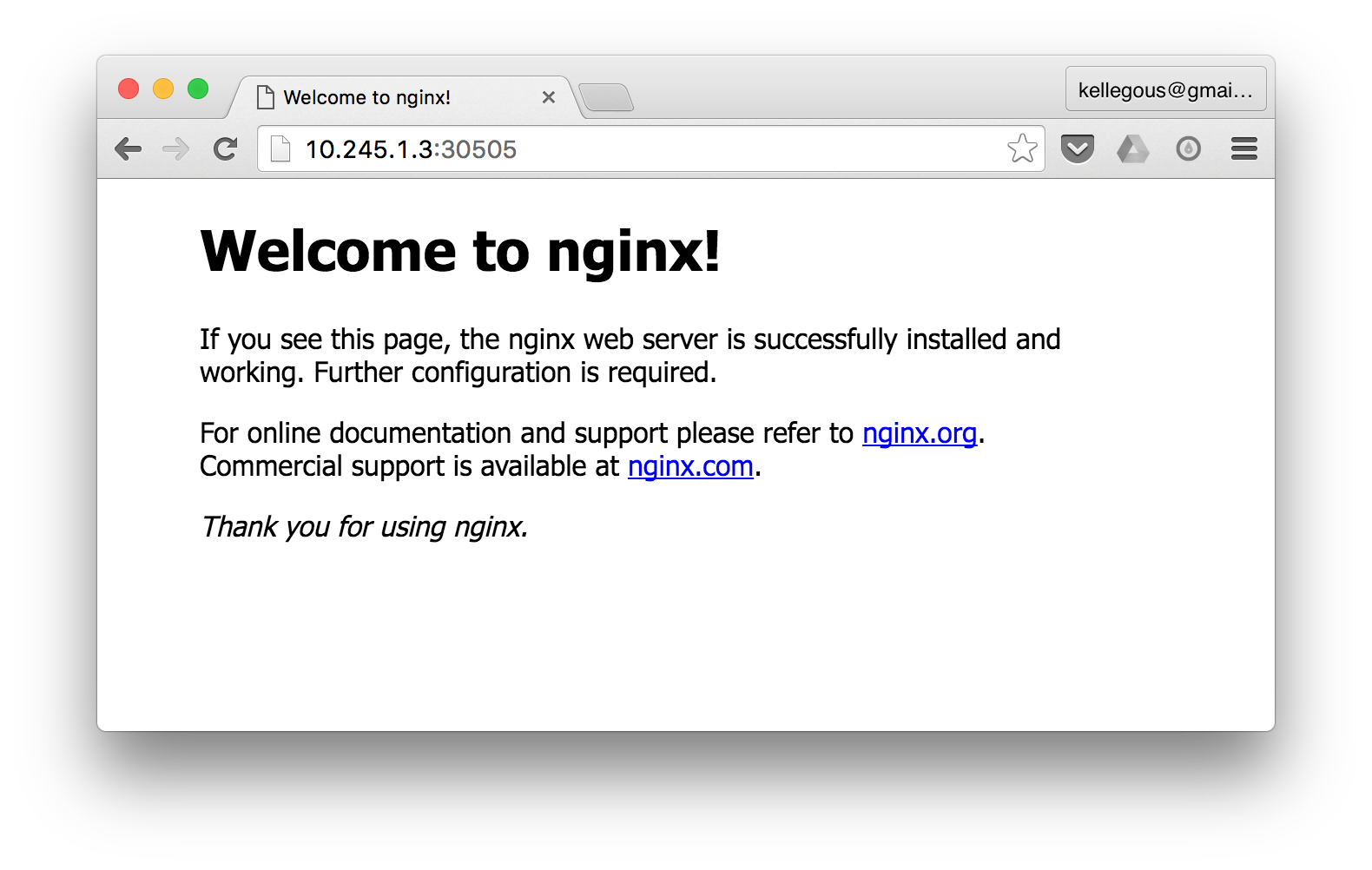

So this post shows you how you can actually see the nginx welcome pages and thus prove to yourself that you managed to run nginx beyond just trusting what the Kubernetes tools tell you. Just to be clear, though, this post doesn’t try to replace “Running Kubernetes Locally with Vagrant”. I’m just merely filling in one big information hole in that guide, which is how to connect to the nginx servers that you just heroically started in container-space. To make this more helpful to future me, though, I’m going to include all the steps. If you are not me, you should start with the original guide and come back to these steps. So here goes:

Running nginx in Kubernetes Locally with Vagrant

1. Create a Kubernetes cluster with a master and a single node.

$ export KUBERNETES_PROVIDER=vagrant $ curl -sS https://get.k8s.io | bash

2. Start an nginx deployment with 3 replicas.

$ ./cluster/kubectl.sh run my-nginx --image=nginx --replicas=3 --port=80

Unfortunately, this is where the original guide stops. You can see that nginx is running using kubectl, but you have no way to use your browser to load the default welcome page. I thought at first that the authors were just lazy and I tried to steal commands from the non-vagrant guides but I was unable to make it work. Here’s the command that you would expect to use next:

$ ./cluster/kubectl.sh expose deployment my-nginx --port=80 --type=LoadBalancer

This command claims to succeed, but it’s actually doing nothing at all. I didn’t know this until I found a set of issues that revealed that asking for a LoadBalancer in a Vagrant environment was essentially a no-op. It claims to succeed, but you just don’t get a load balancer.

The solution is to replace --type=LoadBalancer with --type=NodePort. NodePort is not as cool, it just means that instead of getting a real external IP address, a port will be allocated on each of your nodes (we only have a single node in this example). While this is convoluted, it will allow us to reach nginx running in our Kubernetes cluster.

3. Exposing nginx as a service

$ ./cluster/kubectl.sh expose deployment my-nginx --type=NodePort

Now, we need to know a couple of other bits of information (1) the IP address of our node and (2) the port that our service got mapped to.

Let’s find the IP Address of our node:

$ ./cluster/kubectl.sh describe nodes | grep Address Addresses: 10.245.1.3,10.245.1.3

The IP Address for our node is 10.245.1.3.

And let’s find the “NodePort”

$ ./cluster/kubectl.sh describe services | grep ^NodePort NodePort: <unset> 30505/TCP

And the NodePort is 30505.

So we can reach nginx in the browser by visiting the address: http://10.245.1.3:30505/.

You can see why that is a lot less satisfying than running this in the cloud and getting a real IP Address, but for those who are excessively cheap like I am, http://10.245.1.3:30505 will do just fine.